Gotta Have Some Faith In The Sound: Prejudice Is Still Worth A Listen, 25 Years Later

by MJ on Sep 9, 2015 • 8:28 am 3 CommentsI don’t think there was a more highly anticipated album released in 1990 than George Michael’s Listen Without Prejudice, Vol. 1. The former Wham! frontman was barely two years removed from the gargantuan success of his debut solo effort, Faith. That album took home a Grammy for Album of The Year, spawned 6 top 5 singles, and was a then-rare reverse crossover smash, topping Billboard’s R&B Albums chart. By the end of 1988, the singer/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist had achieved a level of notoriety reserved for only a small handful of contemporaries: Michael, Madonna, Bruce, Prince and Whitney. He was a legend before his 30th birthday.

Think of those artists and how they followed their biggest successes. Whitney, Michael and Madonna stuck to the script, releasing shiny collections of Top 40 radio goodness with Whitney, Bad, and True Blue (respectively). Prince went super-weird with the psychedelic-funk flavor of Around The World In A Day, while The Boss looked inward and emerged with the divorce-themed epic Tunnel Of Love. One may have expected George to follow Faith with a similar collection of dance jams and romantic ballads, but Listen Without Prejudice had more in common with Tunnel Of Love than any of the other albums mentioned in this paragraph. It was a serious, largely somber affair that freaked out a lot of casual fans expecting another “I Want Your Sex”, but it’s arguably held up better than a chart-centric album would have (and certainly has held up as well as if not better than almost all of the follow-ups listed above).

Think of those artists and how they followed their biggest successes. Whitney, Michael and Madonna stuck to the script, releasing shiny collections of Top 40 radio goodness with Whitney, Bad, and True Blue (respectively). Prince went super-weird with the psychedelic-funk flavor of Around The World In A Day, while The Boss looked inward and emerged with the divorce-themed epic Tunnel Of Love. One may have expected George to follow Faith with a similar collection of dance jams and romantic ballads, but Listen Without Prejudice had more in common with Tunnel Of Love than any of the other albums mentioned in this paragraph. It was a serious, largely somber affair that freaked out a lot of casual fans expecting another “I Want Your Sex”, but it’s arguably held up better than a chart-centric album would have (and certainly has held up as well as if not better than almost all of the follow-ups listed above).

Only 27 when Listen was released, George was determined to grow beyond his pop-idol roots with this album’s songs. He was saddled with a bit of a one-dimensional image as a pin-up heartthrob, and wanted to be seen as more than designer stubble and leather jackets. He wanted to be taken seriously as a songwriter. Stung by criticism he received by virtue of his success in R&B circles (by artists ranging from Gladys Knight to Freddie Jackson), George struggled to incorporate his soulful influences without seeming insincere. Most notably, the singer began to take his first tentative steps out of the closet-dropping lyrical hints about his sexuality more than a half decade before the infamous “bathroom incident” at Will Rogers Memorial Park in Beverly Hills.

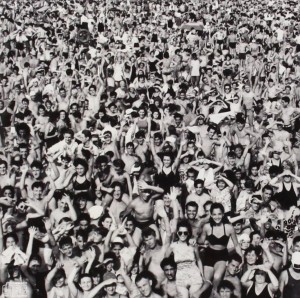

Listen put George’s considerable songwriting skills on full display. Earlier songs ranging from “Careless Whisper” to “One More Try” earned comparisons to Elton John and The Bee Gees, and by 1990, George’s lyricism had fully matured. The album’s centerpiece, “Freedom ’90” (titled so as not to be confused with the Wham! hit from five years prior), was as passionate a statement of purpose as any song ever released. It was also wistful, funny, and hooky. The song only hit #8 on the pop charts despite going Gold and having a video that became iconic. In the clip, George symbolically says goodbye to his past (blowing up the infamous “Faith” jukebox and setting the leather jacket he wore in the video on fire) while a bevy of supermodels saunter around being sexy. In retrospect (and to astute eyes and ears), it also reads as an unofficial “coming out” letter, albeit one set to a funky beat. Oh yeah, and George didn’t appear in one frame of the video. More on that later, though.

Some critics faulted Listen for being too maudlin, and I get that. The album is not a cheery listen, and may have been better accepted in a post-Cobain world where the cheery tones of the top 40 were occasionally undercut by songs with not-so-happy sentiments. The only real false chord for me is struck with the dispassionate, droning “Something To Save”. Every other song is a winner-including a note-perfect cover of Stevie Wonder’s dramatic “They Won’t Go When I Go”.

Elsewhere, George indulges his Beatles fascination with the Lennon-esque “Praying For Time” (which topped the charts on George’s momentum alone) and the expert McCartney rip “Heal The Pain” (George would later re-record the tune with Macca himself). “Waiting For The Day” (which Justin Timberlake’s recent “Not A Bad Thing” is suspiciously reminiscent of) matched an infamous drum loop (James Brown’s “Funky Drummer”) with acoustic guitars five years before Sheryl Crow and Alanis Morissette made it cool, while “Mother’s Pride” is a haunting account of a family struck by the atrocities of war. It became a radio hit after the Gulf War broke out shortly following Listen‘s release. I guess there really isn’t much in terms of lighthearted fare on this album, although the reggae-spiced “Soul Free” ends the album (minus a short closing interlude called “Waiting”) on an up note.

What resonated with me then, as a 14 year old high school sophomore, and what still resonates with me today, is the honesty that Listen projects. It’s difficult to imagine a pop star at that age making an album this personal these days–with the exception of Adele, who clearly owes a massive debt of gratitude to George. I guess the other obvious comparison to George would be Sam Smith, but the simpering mediocrity of In The Lonely Hour is barely the equal of George’s weakest effort, much less an album as meaningful of Listen Without Prejudice.

There is a lengthy list of albums that didn’t get their proper due upon release, and all things considered, Listen Without Prejudice didn’t get that raw a deal. The album was eventually certified double-platinum in the U.S. and was well-received around the world. George didn’t help matters much by refusing to appear in videos, participating in very few interviews, and mounting a tour largely based on covers of other peoples’ material. The album’s release arguably heightened George’s tendency to (depending on how you look at it) fall into bad luck or be his own worst enemy. I mean, look at all the man has endured in the years since: the premature passing of a partner, a protracted legal battle with his label (that resulted in a six year gap between albums), the park incident and subsequent public shaming (which George handled like a champ in a much-less homo friendly and sex-negative environment), the derailment of his career in America, drugs, jail time, two near-death experiences and now…who knows? Reports alternately state that George is doing fine and enjoying life as a semi-private citizen and that he’s drug-addled and close to death. He pops up on Twitter every once in a while (most recently to celebrate Listen‘s anniversary) but hasn’t released an album of new music in over a decade. The level of unfulfilled promise that registers when looking at the last fifteen years of George’s creative life is stunning-and sad.

However, most people never make one classic album, let alone two. After all of the public foibles are forgotten, the music will remain. Hopefully, listeners in the years to come take the album’s title to heart.

3 comments

John says:

Sep 9, 2015

Excellent write-up, and really captures what I found fascinating about this release. I don’t know if you ever got around to checking out Tommy Mottolla’s Hit Man, but he talks about the Listen era and the drama that surrounded it. Here’s hoping George decides to share his life story at some point.

MJ says:

Sep 9, 2015

I haven’t read the Mottolla book. If it’s anything like the Clive Davis book, I might have to pass! 🙂

Nah, I’ll check it out…maybe it’s on Amazon cheap.

Alec says:

Sep 14, 2016

I mostly agree, except “Something to save”. This is a wonderful piece of a song. The whole album is very harmonious and handmade. The lyrics are serious and profound. This album is one of his best, together with Older.