One of the last and all-time greatest musicians who was around at the invention of rock ‘n’ roll and still kicking in 2013, Paul McCartney is a legend. He’s released more singles than just about any artist in music history, and is by far the most prolific Beatle (not necessarily fair in Lennon’s case, but he probably still would’ve been had Lennon made it this far). He was the centerpiece of last year’s kaleidoscopic Olympics ceremony, he recorded with Michael Jackson in the Thriller era, he did a voice on The Simpsons, was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. Seems like he’s popped up in every cultural happening of the past 50 years, Forrest Gump-style. That his latest album, at the age of 71 no less, isn’t the topic of everyone’s conversation this month would seem squarely the blame of our exponentially expanding, fractured culture – there’s just so much out there now, and so many private niche circles in which fans can nestle, that even our oldest king of music can go overlooked by most people at this point, right? Lost in the shuffle? Wrong. McCartney brought it on himself: that prolificacy of his has been a double-edged sword. On the one hand, if your close your eyes and connect McCartney’s familiar voice to his work in the Beatles, all of his post-Beatles work – from Wings to all those solo albums – can aurally transform into a ridiculously generous helping of “what would The Beatles sound like if they hadn’t broken up? (and if Paul became the lone singer and songwriter)” It’s all part of the Beatles family tree, and for those who recognize the Fab Four as THE band, listening to Paul’s solo work can be a fascinating study in comparison analysis, trying to root the DNA of his ’60s work out of each new song he recorded in the ’70s and beyond. On the other, bitchslapping hand, this unending geyser of songs has revealed one of the most long-running, headache-inducing cases of wandering, unsatisfying, what-the-hell-is-he-thinking solo-impotency the music industry has ever seen. His solo career hasn’t been bad, but it’s astonishing how little of it deserves preservation. You’d think the guy who wrote “Can’t Buy Me Love” and “Hey Jude” would have a reservoir of melodies to last him a lifetime, but if you ask me, put all of his 24 post-Beatles albums together (not counting the classical ones or The Firemen, both of which belong in categories all their own) and while you’d be up to your ears in readily likable tunes, filling out even a single-disc, standard 14-track Best-Of comp would be a struggle. Perhaps a reappraisal of his catalog is in order, but until then, it is notorious for its spotty, vaguely disappointing makeup. While McCartney has tried numerous approaches to his music, neither most of his hit singles (“Band on the Run”, “Listen to What the Man Said”, “Let ’em in”, “My Brave Face”) nor his deep cuts can be considered all that special, much less timeless and brilliant like so much he did for The Beatles. At best I’d call his better songs solid, catchy, occasionally interesting, but with a few exceptions (“Maybe I’m Amazed”, “Live and Let Die”, half of Ram), they never seize upon that combustion of ambitious songwriting and habit-forming melodicism that made him a legend in the first place. If pursuing this different kind of muse has yielded him a satisfying career in the wake of his Fab Four days, then good for him, but as a listener, even after hearing every Beatles song 200 times, I’d still reach for one of those albums before any of his later work. And it’s not that everything he did after 1970 need be held up to Abbey Road standards; plenty of artists have transitioned from band member in a famous group to a superior Act II as a lone wolf: Michael Jackson, Van Morrison, Neil Young, Paul Simon, arguably George Michael, Iggy Pop, Billy Idol, Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins, Beyonce, Justin Timberlake, etc. etc. While Paul McCartney has led the longest-lasting and most spotlighted career of any rock band survivor to date, a lot of it has been muddled, forgettable, misguided, and uninspired.

One of the last and all-time greatest musicians who was around at the invention of rock ‘n’ roll and still kicking in 2013, Paul McCartney is a legend. He’s released more singles than just about any artist in music history, and is by far the most prolific Beatle (not necessarily fair in Lennon’s case, but he probably still would’ve been had Lennon made it this far). He was the centerpiece of last year’s kaleidoscopic Olympics ceremony, he recorded with Michael Jackson in the Thriller era, he did a voice on The Simpsons, was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. Seems like he’s popped up in every cultural happening of the past 50 years, Forrest Gump-style. That his latest album, at the age of 71 no less, isn’t the topic of everyone’s conversation this month would seem squarely the blame of our exponentially expanding, fractured culture – there’s just so much out there now, and so many private niche circles in which fans can nestle, that even our oldest king of music can go overlooked by most people at this point, right? Lost in the shuffle? Wrong. McCartney brought it on himself: that prolificacy of his has been a double-edged sword. On the one hand, if your close your eyes and connect McCartney’s familiar voice to his work in the Beatles, all of his post-Beatles work – from Wings to all those solo albums – can aurally transform into a ridiculously generous helping of “what would The Beatles sound like if they hadn’t broken up? (and if Paul became the lone singer and songwriter)” It’s all part of the Beatles family tree, and for those who recognize the Fab Four as THE band, listening to Paul’s solo work can be a fascinating study in comparison analysis, trying to root the DNA of his ’60s work out of each new song he recorded in the ’70s and beyond. On the other, bitchslapping hand, this unending geyser of songs has revealed one of the most long-running, headache-inducing cases of wandering, unsatisfying, what-the-hell-is-he-thinking solo-impotency the music industry has ever seen. His solo career hasn’t been bad, but it’s astonishing how little of it deserves preservation. You’d think the guy who wrote “Can’t Buy Me Love” and “Hey Jude” would have a reservoir of melodies to last him a lifetime, but if you ask me, put all of his 24 post-Beatles albums together (not counting the classical ones or The Firemen, both of which belong in categories all their own) and while you’d be up to your ears in readily likable tunes, filling out even a single-disc, standard 14-track Best-Of comp would be a struggle. Perhaps a reappraisal of his catalog is in order, but until then, it is notorious for its spotty, vaguely disappointing makeup. While McCartney has tried numerous approaches to his music, neither most of his hit singles (“Band on the Run”, “Listen to What the Man Said”, “Let ’em in”, “My Brave Face”) nor his deep cuts can be considered all that special, much less timeless and brilliant like so much he did for The Beatles. At best I’d call his better songs solid, catchy, occasionally interesting, but with a few exceptions (“Maybe I’m Amazed”, “Live and Let Die”, half of Ram), they never seize upon that combustion of ambitious songwriting and habit-forming melodicism that made him a legend in the first place. If pursuing this different kind of muse has yielded him a satisfying career in the wake of his Fab Four days, then good for him, but as a listener, even after hearing every Beatles song 200 times, I’d still reach for one of those albums before any of his later work. And it’s not that everything he did after 1970 need be held up to Abbey Road standards; plenty of artists have transitioned from band member in a famous group to a superior Act II as a lone wolf: Michael Jackson, Van Morrison, Neil Young, Paul Simon, arguably George Michael, Iggy Pop, Billy Idol, Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins, Beyonce, Justin Timberlake, etc. etc. While Paul McCartney has led the longest-lasting and most spotlighted career of any rock band survivor to date, a lot of it has been muddled, forgettable, misguided, and uninspired.

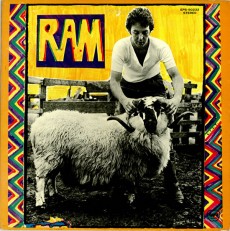

Yet taking into account the volume of greatness he produced with The Beatles and the fact that he’s kept going for over forty years hence, the inconsistency of his discography is forgivable to a large extent, and it’s still exciting when he offers something new. Like Woody Allen, you keep hoping he’ll reign in his bad habits, stop repeating himself, and surprise us with another home-run akin to his glory days. Unlike Woody Allen, who actually does hit a cinematic home-run every half decade or so, it’s a safe bet that at 71, after two dozen albums of mixed success, Paul McCartney will never come up with a monolithic, show-stopping solo album that we can all agree on. Ram was his high point in 1971, and while many go to bat for McCartney, McCartney II, and Band on the Run, my own personal indifference to all three – even as a hardcore Beatles fan and avowed Team Paul guy (all due respect to John, but Paul was the best one all around) – is indicative of their unstable reputations. Not everybody loves and salutes those ones, but McCartney disciples are legion, so apologists abound, and I’m sure blood and sweat has been poured into convincing cases of every second of sound the man has ever recorded. Alongside Bob Dylan, he’s our eldest statesman of pop music, a face of the original zeitgeist, one of the only leaders in music royalty who was there from the very beginning.

Yet taking into account the volume of greatness he produced with The Beatles and the fact that he’s kept going for over forty years hence, the inconsistency of his discography is forgivable to a large extent, and it’s still exciting when he offers something new. Like Woody Allen, you keep hoping he’ll reign in his bad habits, stop repeating himself, and surprise us with another home-run akin to his glory days. Unlike Woody Allen, who actually does hit a cinematic home-run every half decade or so, it’s a safe bet that at 71, after two dozen albums of mixed success, Paul McCartney will never come up with a monolithic, show-stopping solo album that we can all agree on. Ram was his high point in 1971, and while many go to bat for McCartney, McCartney II, and Band on the Run, my own personal indifference to all three – even as a hardcore Beatles fan and avowed Team Paul guy (all due respect to John, but Paul was the best one all around) – is indicative of their unstable reputations. Not everybody loves and salutes those ones, but McCartney disciples are legion, so apologists abound, and I’m sure blood and sweat has been poured into convincing cases of every second of sound the man has ever recorded. Alongside Bob Dylan, he’s our eldest statesman of pop music, a face of the original zeitgeist, one of the only leaders in music royalty who was there from the very beginning.

That’s why New, like every latest Dylan album, has already been showered in adulation. This could very well be the final testament of history’s biggest music star; ‘twould be disrespectful not to cherish every moment of it, right? I was as tickled as anyone when the title track dropped a month ago, and it sounded so much like a lost Beatles song that my mind raced with conjecture at the possibilities for the album itself. I should’ve remembered that Paul often excels at first impressions, given the strength of his many other lead singles, and prepared myself for another round of his stock concoctions. Because despite what many major critics have claimed in the past week, there is nothing revolutionary, especially fresh, or heretofore unexplored about the misleadingly titled New – while everyone will find a few gems for their own, depending on your song flavors of choice, it unfortunately replicates the too-familiar McCartney formula of blandly jovial pop/rock and sometimes flat, half-assed filler. Whether he really only used half of his ass to write and produce these songs or in fact plunged headfirst with creative, passionate mania is beside the point (sidebar: according to interviews, it was more of a newly wedded inner bliss, though that state of mind better describes 1970’s McCartney and 1971’s Wings debut Wild Life than this one). Structurally and sonically, listening to New is like listening to a polished redux of Venus and Mars – hummable in pieces, a couple frolicsome piano-led tracks, the occasional blazed-out rocker, leaving you in moderately cheerful spirit if not the least bit satisfied beyond the surface. So YMMV – for anyone who’s enjoyed an earlier Paul McCartney album, this won’t let you down. It’s more of the same. I just wish he had something more definitive to sing about and would do so in a more engaging style. But since we critics are tasked with evaluating with what’s on the table, not what we wish was there instead, I digress.

That’s why New, like every latest Dylan album, has already been showered in adulation. This could very well be the final testament of history’s biggest music star; ‘twould be disrespectful not to cherish every moment of it, right? I was as tickled as anyone when the title track dropped a month ago, and it sounded so much like a lost Beatles song that my mind raced with conjecture at the possibilities for the album itself. I should’ve remembered that Paul often excels at first impressions, given the strength of his many other lead singles, and prepared myself for another round of his stock concoctions. Because despite what many major critics have claimed in the past week, there is nothing revolutionary, especially fresh, or heretofore unexplored about the misleadingly titled New – while everyone will find a few gems for their own, depending on your song flavors of choice, it unfortunately replicates the too-familiar McCartney formula of blandly jovial pop/rock and sometimes flat, half-assed filler. Whether he really only used half of his ass to write and produce these songs or in fact plunged headfirst with creative, passionate mania is beside the point (sidebar: according to interviews, it was more of a newly wedded inner bliss, though that state of mind better describes 1970’s McCartney and 1971’s Wings debut Wild Life than this one). Structurally and sonically, listening to New is like listening to a polished redux of Venus and Mars – hummable in pieces, a couple frolicsome piano-led tracks, the occasional blazed-out rocker, leaving you in moderately cheerful spirit if not the least bit satisfied beyond the surface. So YMMV – for anyone who’s enjoyed an earlier Paul McCartney album, this won’t let you down. It’s more of the same. I just wish he had something more definitive to sing about and would do so in a more engaging style. But since we critics are tasked with evaluating with what’s on the table, not what we wish was there instead, I digress.

For those jonesing for any kind of Beatles connection or tribute, both the aforementioned “New” and the nostalgic “Early Days” apply. The former is a yummy mash-up of “Getting Better” and the harpsichord in “Piggies”; the effortless elegance of its melody, rhythm, and flow aren’t just Beatlesque but McCartneyesque. Sunny romanticism with a bit of self-effacement stirred in, deceptively simple in execution yet charming, bouncy, and playful, and even ending with a lovely old-fashioned coda. Why hasn’t this Paul come out to play more often in the past few decades? Meanwhile, “Early Days” is a plaintive memory lane trip, apparently about his pre-fame days hanging out with John Lennon. Lyrically it mirrors Ringo Starr’s 2008 remembrance parade Liverpool 8, while musically operates on the same stark, wistful melodicism as “Dance Tonight”, the highlight of Paul’s previous album (2007’s Memory Almost Full) and could easily be used in the opening credits of a hushed indie dramedy. Wise was the move to get producer Ethan Johns on this one, with his penchant for bringing out the folk beauty in artists like Laura Marling, Ray LaMontagne, Paolo Nutini, and Ryan Adams.

But they can’t all be winners, and the other Johns-assisted track is “Hosanna”, the album’s weakest. That it’s also the only other song with no spring in its step or aggression in its bones is probably just a coincidence – Paul can do quiet and contemplative as well as anyone, but “Hosanna” remains forgettable no matter how many times you listen to it, and despite all of its overcompensating studio sound effects like dubs, echoes, and backward loops. Adele’s guru Paul Epworth punches up the two loudest efforts, opener “Save Us”, a storming “Live and Let Die” descendant, and stomping anthem “Queenie Eye”, but he too misfires in the album’s second half with meandering closer “Road”, sounding like a discarded Depeche Mode exercise. It only grabs your attention during its wordless chorus duet between handclaps and a striking lower register piano hook. Not sure why they couldn’t add vocals to this part and make it sound less like a rough draft, though.

Besides Mark Ronson’s work on “New” and “Alligator” (an overstuffed patchwork that engages in small parts with its hard guitar line, backing “doo doo doo”s, and more harpsichord, but feels incohesive), the rest of New goes to George Martin’s song Giles, of course. Though he’s proven a chip off the old block by playing a major part in the 1996 Beatles Anthology, the Cirque du Soleil Beatles show Love, the Beatles Rock Band edition, and Scorsese’s George Harrison documentary Living in the Material World, this is his first collaboration with Paul, and it plays out well enough, but you’d be forgiven for expecting better results. “On My Way to Work”, a mostly acoustic number offset by towering electric interludes that threaten to take the song in a propulsive direction it never commits to, is another ruminative time travel track to his humble beginnings, when he worked for a delivery service in Liverpool – this long-distance reminiscing is the closest we get to any acknowledgement of mortality from the septuagenarian, which is probably a compliment to him considering the excess of “death is looming”-themed albums from aging musicians. It’s about halfway to being a legitimately good song, but doesn’t make it (pattern detected…), basically the same way to sum up “Looking at Her” (thrilling: the post-chorus section with its scraping synths and tambourine; underwhelming: the subdued electro arrangement in the first half) and the kinda catchy “Everybody Out There”. “Appreciate” is the most I can do for the song of the same name on here, which takes a kooky, cluttered, country-hip hop direction that could almost be mistaken for a Beck composition. Interesting try, at least. “I Can Bet” aims to be a winner, but it sounds so much like “Turned Out”, a b-side available on the album’s deluxe edition, that it merits some scorn for having displaced its highly preferable clone for whatever reason. “Turned Out” is ’80s power pop all the way, a bright, concise, 3-minute hip-shaker that owes Dave Edmunds and The Cars a tip of its hat. It’s easy to see why fellow deluxe edition castaway “Get Me Out of Here” isn’t part of the canon, with its vocal affectation (echoes of a lot of his annoying earlier solo stuff) and trite lyrics about his entitlement as a celebrity virtually guaranteeing that this was something he wrote while stuck in traffic, but Paul should’ve been proud to include “Turned Out” on the main version for everyone to hear.

Finally, there’s a hidden track called “Scared” but what is the point of this gimmick anyway? If you went to the trouble to put the song on the official album and even name it, why does it need to be tacked on as an “invisible”, inseparable ellipsis to the last track? He even claims it’s one of his favorite recordings for New, so again, why make it a nuisance? As a stripped-down piano lament, it would’ve made a perfectly clichéd closing track. So let’s just go ahead and skip all analysis of that one. It’s not worth the time.

New isn’t much more or less entertaining than the typical Paul McCartney endeavor. He’s still got an adventurous side, and an ear for earworms, and the finest producers and studio mixing boards money can buy, so there’s little chance that you can’t find something about this to relish, whatever your angle may be. But except for the conveniently singled-out title song, there’s just no indelible magic to it, nothing essential or peerless about his work. There’s this journeyman sensibility that doesn’t do the Walrus justice at all. It might be asking too much of a man who has probably written over 1,000 songs in his lifetime, many of which rank amongst the most popular and beloved of all time, but I’ll just never get the hang of settling for good enough from the guy who wrote “Eleanor Rigby”.

7 comments

Chris says:

Oct 15, 2013

“while you’d be up to your ears in readily likable tunes, filling out even a single-disc, standard 14-track Best-Of comp would be a struggle”

Here you go (in chronological order):

1. Maybe I’m Amazed*

2. Junk*

3. Every Night

4. Too Many People*

5. Ram On

6. Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey*

7. Heart Of The Country

8. The Back Seat Of My Car*

9. Tomorrow

10. Give Ireland Back To The Irish

11. My Love

12. When The Night

13. Live And Let Die*

14. Band On The Run*

15. Jet*

16. Bluebird

17. Mrs. Vanderbilt

18. Let Me Roll It*

19. Mamunia

20. No Words

21. Helen Wheels

22. Picasso’s Last Words (Drink To Me)

23. Nineteen Hundred And Eighty Five

24. Venus And Mars/Rock Show*

25. Call Me Back Again

26. Listen To What The Man Said

27. Let Em In*

28. Silly Love Songs*

29. Coming Up

30. Waterfalls

31. Tug Of War

32. Here Today*

33. Ebony And Ivory*

34. Say Say Say

35. My Brave Face

36. Flaming Pie

37. Calico Skies

38. Run Devil Run

39. What It Is

40. Fine Line

41. Jenny Wren*

42. This Never Happened Before

43. Vintage Clothes*

44. House Of Wax

45. New

* denotes the ones I would include on a single Best Of disc

Mike Browne says:

Oct 16, 2013

Yeah, I didn’t think I’d get unanimous agreement with that one, but to each their own. No “Eat at Home” on that list? That song’s a treat. Given my obsession with all things Beatles though, thanks for the list. I’m going to re-listen to a lot of those songs and try to make my own (most of the ones you earmarked for the best-of disc I would choose too so we have more in common than you might think)

MJ says:

Oct 16, 2013

I’d give Paul a 20-track best of comp, but I must say I, like you, find his solo work a steep drop off from the Beatles days. Every Beatles album from “Help!” forward is a must-own. I can’t say the same about any of macca’s solo albums. And while I was somewhat intrigued by the appearances of Epworth and Ronson, I can’t say that I’m too psyched to actually give “New” a listen after reading this most excellent review. Kudos.

Jeff says:

Oct 16, 2013

This perfectly sums up my opinion on Paul’s solo output on the whole.

I was talking with a friend once and she observed that the Beatles were genius together but not genius solo. i respectfully disagree. To me, John Lennon’s first two solo albums (Plastic Ono Band and Imagine) and George Harrison’s solo debut (All Things Must Pass) stand with any of their group work. Ringo Starr had several good songs. But he never made a truly great album.

Paul has made a lot of albums, some are very good (Ram, Band On The Run, Flaming Pie, Run Devil Run) some are okay and there are a lot of mediocre ones. But he has yet to make a masterpiece that stands with his Beatles work. And he may never do so.

To me a lot of his post Beatles output was dominated by trendhopping. Obvious attempts to make music targeted at markets not as a means of expression. For instance, while I enjoyed Say Say Say, his other Michael Jackson collaboration The Girl Is Mine came off like a calculated attempt to get a song on MTV.

Trey Stone says:

Oct 18, 2013

I think Lennon and McCartney are really close in their Beatles work but the more I’ve listened the more I’ve agreed with the idea that Paul’s the better melodist of the two. Like regardless of which one’s a better song “Penny Lane” feels more complete to me than “Strawberry Fields Forever,” to use an example.

I own “McCartney” and “Ram,” don’t really know what’s considered his best stuff after that besides “Band on the Run”

MJ says:

Oct 18, 2013

…but “The Girl Is Mine” didn’t have a video…

Gonzo says:

Oct 18, 2013

Mike Browne-this is truly one of the best reviews that’s ever run on this site. Fantastic job.

As for the debate:

I think that excepting Ringo (poor guy), all of the lads have albums that stand on their own. Plastic Ono Band, Imaging, McCartney, Ram, Band on the Run, All Things Must Pass, maybe even Living in the Material World.

Still, Jeff’s comment got me thinking: really, truthfully, are there people who are into solo Beatles work that don’t give a damn about the group’s corpus? I’m sure they’re out there, but I can’t see them being too numerous. All of this is to say to what extent to any of their solo albums truly ‘stand on their own?’ Just as their solo work is in some ways a continuation of their work with the group, isn’t our appreciation of those solo discs merely a continuation of our fandom for the group’s work?