“Chronicle” made 22 million last weekend in the U.S. domestic box office. That’s not bad considering it’s a film cast with relatively unknown actors and for a film released in the dead season of February. This is far more impressive when considering it cost only 12 million to produce the film. How did such a film get away with such a small budget and still bring in a large audience on its opening weekend? The answer can most likely be found by looking into how the film was shot, and not necessarily the story, themes, or the talent involved.

“Chronicle” made 22 million last weekend in the U.S. domestic box office. That’s not bad considering it’s a film cast with relatively unknown actors and for a film released in the dead season of February. This is far more impressive when considering it cost only 12 million to produce the film. How did such a film get away with such a small budget and still bring in a large audience on its opening weekend? The answer can most likely be found by looking into how the film was shot, and not necessarily the story, themes, or the talent involved.

Often dismissed as a “gimmick,” the found footage aesthetic is one of the more recent tropes of filmmaking. As a product of the “YouTube Generation,” you have to acknowledge that almost everything is caught on film these days. Therefore, it only seems logical for Hollywood and independent filmmakers to take advantage of this micro-budget technique, simultaneously saving themselves loads of money and tapping into a strong aspect of popular culture (just think about how much time in your average day that you’re on virtual media sites like YouTube, Vimeo, etc.). Conversely, that’s not to say that filmmakers of the past haven’t experimented with this aesthetic long before the advent of the home video camcorder or cellphone camera. Orson Welles‘ “F for Fake” combined both real and staged footage to blend an interesting faux-documentary and quasi-existential introspective on how film can trick the audience into believing what is real and what is not. Films dabbled with the concept throughout the 1980’s; however, with the film entitled “The Blair Witch Project” being released in 1999 and the astounding box office numbers it made on such a tiny budget ($60,000), the found footage aesthetic would soon become a mainstay in Hollywood, foreign, and independent filmmaking.

But why horror? I asked our resident PopBlerd! horror movie junkie, Andrew, to share his thoughts on why the found footage aesthetic translates so well into the genre…

I think the found-footage aesthetic really enhances genuine scares. I was thinking about this when I rented the new “Paranormal Activity” movie a week or so back. I spent a lot of that movie genuinely on edge, even when nothing of note was happening on-screen. There’s some voyeuristic x-factor at play when a shot is pared down to its bare essentials; perhaps it’s because subconsciously, we’re used to horror films that tell us when we’re supposed to be scared. Slow zooms, ominous cinematography, obvious musical cues… We’ve become conditioned by cinema itself to react to certain things. Movies like this, that typically strive for a realistic approach to the often-fantastical events on screen, don’t give us the benefit of cinematic trickery to let us know that hey, something’s about to go DOWN. By that notion alone, it’s a brilliantly effective device.

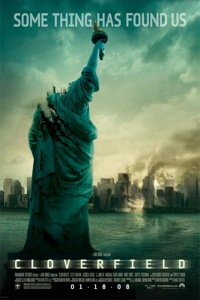

It’s also effective financially. There’s a reason why Paranormal Activity 4 has already been green-lit for an October 2012 release. It’s a low risk scenario for studios to film a relatively easy shoot with very inexpensive productions costs (i.e. contained set locations, using no-name actors, short filming schedule, etc.) and the audience has already established that they will pay for a found-footage movie, regardless of it’s critical reception and/or quality (“The Devil Inside” averaged an abysmal 5% Rotten Tomato rating, but went on to rake in 35 million on its opening weekend). Other very successful horror films relied heavily on this aesthetic, such as 2007’s “[Rec]” (and its subsequent American remake “Quarantine”) and, arguably more of a monster movie than horror, 2008’s “Cloverfield.” Other genres have dabbled with found footage, including comedy, action, and drama; nevertheless, elements of this aesthetic can be found in the majority of most films today.

In spite of the logical and financial merits behind producing these films, I’m a bit down on the idea. For me, this technique usually brings me out of the film more often than not, making me well aware of the filmmaking and less immersed in the actual events unfolding on screen (which is the antithesis of what this technique intends on delivering). Secondly, half of these films are spent acknowledging or explaining away the presence of the camera. “Is it alright if we film this?” “Why are we on camera?” “Are you filming this?!?” A lot of screen time is taken away from more important storytelling elements such as plot and character development. On top of this, some films even break the rules they establish in limiting the audience’s perspective (e.g. “District 9“) and further pull me out of the immersion the filmmakers intend to create when using this technique. There’s also the motion sickness argument, where most people can’t handle the Greengrass-esque “shaky cam” techniques which are heavily featured in these films. Lastly, there’s the more potentially pretentious argument that these techniques are bastardizing the “high art” of cinema (I won’t go into that argument now to save me from sounding like some turtle-neck donning film nerd discussing the merits of Godard and the French New Wave while sipping on an espresso). Regardless, elements of the found footage aesthetic will remain in cinema as long as the audience is paying for it. What do you think of the found-footage aesthetic? Is it a legitimate genre or cheap gimmick? Sound off in the comments below!