The release of Man of Steel – the latest attempt to tell the story of comic book legend Superman – fills me with an excitement I can’t quite articulate. The chance to see my favorite mythological figure in American history grace the silver screen again is a cause for celebration – which is astounding, considering how little I wanted to do with this particular tale mere months ago.

The release of Man of Steel – the latest attempt to tell the story of comic book legend Superman – fills me with an excitement I can’t quite articulate. The chance to see my favorite mythological figure in American history grace the silver screen again is a cause for celebration – which is astounding, considering how little I wanted to do with this particular tale mere months ago.

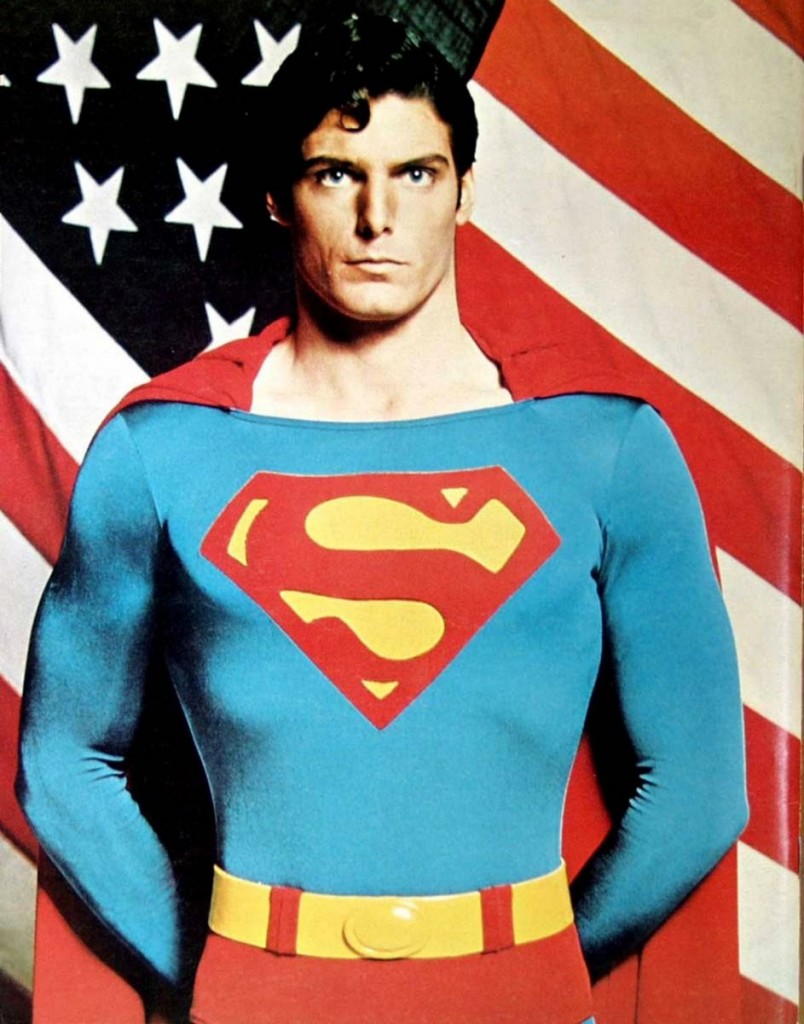

Since the last son of Krypton flew into my life, I’ve had one very specific picture of him in my head: the imposing but safe figure of Christopher Reeve, donning the blue tights and red cape and happily thwarting major disasters to the tune of John Williams’ majestic fanfares. Unlike his Justice League cohort Batman, he did not brood nor question why he was doing what he did. He just did it. That’s a hell of an ideal to aspire to.

By contrast, the hero in Zack Snyder’s new film seems to fit more in line with our modern Batman, as put on film by director Christopher Nolan in a superb trilogy of films from 2005 to 2012. (Nolan is the producer of Man of Steel, the screenplay of which is written by David S. Goyer, who received story credits on all three Batman films and wrote the screenplay for Batman Begins.) This Superman does seem to have some angst, as a survivor of a long-gone planet unsure of how to process his extraordinary skills.

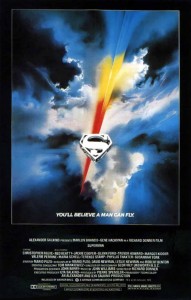

As strange as it is to imagine a Superman truly overwhelmed by ennui, one thing has become very clear of late: Man of Steel – not to mention literally every other comic book movie that’s made the rounds in the past decade-plus – has the first Reeve-led adventure, 1978’s Superman: The Movie, to credit for its existence.

The legend of Superman, both in media and real life, has only captivated me in recent years. As a child, it was Batman who filled my head with spectacular images (thanks to the Tim Burton films and the astounding animated series of the early 1990s) and filled my toy box with action figures, plastic dress-up gear and other paraphernalia.

I didn’t really pay attention to many comic-based heroes again, until a chance viewing of Superman: The Movie in high school. A delightful counterpoint to Batman’s brooding, Kal-El – as portrayed expertly by Christopher Reeve and director Richard Donner – was a stunning ideal. He was easygoing and casual, as able to subdue a nuclear missile as he could warm the heart of Margot Kidder’s headstrong Lois Lane. And when he looked into Lois’ eyes and said, “I never lie”? I bought it.

But even I was slow to truly grasp my love for Superman: The Movie. Despite my admiration for the film’s technical feats, including the depiction of flight and Williams’ expressive soundtrack, it took some time to realize that Superman is chiefly responsible for the 21st century’s wave of serious-but-entertaining film treatises on superheroes.

Let’s be honest for a minute: comic books have always been kid’s stuff. On screen, one doesn’t have to go further than Adam West’s depiction of Batman to realize this. Superman: The Movie was the first visual media to swing the pendulum in the other direction. Rather than treat Superman as a campy myth to be taken for granted, Donner reminded cast and crew of one word: verisimilitude. He wanted everyone to believe, from craft service to crowds in Kalamazoo, that Superman’s feats really were possible.

The film’s tagline – “You’ll believe a man can fly” – was no accident. Donner’s dedication to that ideal had stunning repercussions onscreen and even off; were it not for that superhero verisimilitude, the world may not have paid as much attention to Christopher Reeve as a victim of (and activist for the cure of) spinal paralysis. We also may not have shed as many tears when he passed away in 2004.

The film’s tagline – “You’ll believe a man can fly” – was no accident. Donner’s dedication to that ideal had stunning repercussions onscreen and even off; were it not for that superhero verisimilitude, the world may not have paid as much attention to Christopher Reeve as a victim of (and activist for the cure of) spinal paralysis. We also may not have shed as many tears when he passed away in 2004.

It’s easy to see how the film successfully set a template for good and mediocre comic-book adaptations. By including lesser-known actors alongside stars in supporting roles, Superman (which billed the virtually-unknown Reeve below Marlon Brando as Superman’s father Jor-El and Gene Hackman as the villainous Lex Luthor) anticipated the pairings of Jack Nicholson and Michael Keaton in Batman or Tobey McGuire and Willem Dafoe in Spider-Man.

But the film’s insistence on setting up Superman’s origin – an arc that takes up an hour of running time – meant nearly every subsequent superhero had to be explained on film, not simply understood as having been explained. It is for this reason that many prefer the considerably more action-packed sequel, Superman II. (For best results, check out Donner’s 2006 “director’s cut”; he’d shot much of Superman and Superman II back-to-back before producers fired him and replaced him with A Hard Day’s Night director Richard Lester. This version of Superman II is as respectful of the source material as its predecessor, while trimming the exposition of the original film and the camp humor that was prevalent in Lester’s version.)

For whatever reason – the general seismic cultural shifts that occur every generation, the less savory cultural effects that happened post-9/11 – Superman: The Movie‘s mix of dewy-eyed reverence and knowing silliness has been overlooked in favor of a crop of more “realistic” superhero flicks. (Case in point: director Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns (2006) – a well-intentioned if lengthy continuation of the series set boldly in the context of the first two Reeve-starred movies – is unfairly considered a flop, despite strong critical marks and a higher box-office intake than Batman Begins.) But therein lies the irony: these modern-day heroes would never have taken flight if Superman: The Movie didn’t give them the wings.