It comes within the first few seconds of the film.

It comes within the first few seconds of the film.

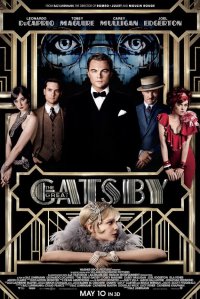

Tobey Maguire, playing Nick Carraway, utters the first lines of The Great Gatsby. Except, they’re not the words as written by F. Scott Fitzgerald. They’re a close approximation — just without the elegance and thematic context.

That’s your first indication that Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of the Fitzgerald classic will be good, but not quite as good as its source material.

But really, how could it be? Gatsby is a book that many (but not everyone) consider the Great American Novel. One that’s been a high-school-reading staple for generations. A novel that seems damned near impossible to adapt in any sort of satisfactory fashion, despite four big-screen attempts (including a 1974 version that starred Robert Redford and Mia Farrow).

So having Nick (and Luhrmann) reset the audience’s expectations right off the bat frees us up to just watch the movie and not be disappointed later.

It’s kind of a smart move, if you think about it.

Social commentary

For those who got through high school without reading Gatsby, or who need a quick reminder, the novel and film tell the story of the titular character (Leonardo DiCaprio), a mysterious millionaire who uses his wealth to, among other things, throw lavish parties that he hopes will one day attract Daisy (Carey Mulligan), his long-lost great love, who has moved on and married another man. It’s all told through the eyes (and words) of Nick Carraway, a Midwestern transplant who lives next door to Gatsby in the new-money West Egg neighborhood out on Long Island — a stand-in for the Hamptons. Across the water, Daisy and her husband, Tom (Joel Edgerton), live in East Egg, home to those with old money.

For those who got through high school without reading Gatsby, or who need a quick reminder, the novel and film tell the story of the titular character (Leonardo DiCaprio), a mysterious millionaire who uses his wealth to, among other things, throw lavish parties that he hopes will one day attract Daisy (Carey Mulligan), his long-lost great love, who has moved on and married another man. It’s all told through the eyes (and words) of Nick Carraway, a Midwestern transplant who lives next door to Gatsby in the new-money West Egg neighborhood out on Long Island — a stand-in for the Hamptons. Across the water, Daisy and her husband, Tom (Joel Edgerton), live in East Egg, home to those with old money.

Fitzgerald used his words to both document the roaring jazz age of the 1920s and the social climbers who made the most of it, and make social commentary about the divide between and the haves and have-nots — themes that still resonate today.

Like one of Gatsby’s parties

Unfortunately, Luhrmann is less concerned with such subtext and meaning, and more interested in the decadent aspects of the story. Not surprisingly, his film plays like a 140-minute version of one of Gatsby’s parties: It’s fun, and it looks good, but it’s all showy, superficial emptiness, and it leaves you with a heck of a hangover.

Unfortunately, Luhrmann is less concerned with such subtext and meaning, and more interested in the decadent aspects of the story. Not surprisingly, his film plays like a 140-minute version of one of Gatsby’s parties: It’s fun, and it looks good, but it’s all showy, superficial emptiness, and it leaves you with a heck of a hangover.

Not that this should be a surprise. Luhrmann is, of course, the director of such films as Romeo + Juliet and the brilliant Moulin Rouge! — the awful Australia too — all of which employed the director’s trademark hyper-kinetic style of filmmaking. Nearly all of the Luhrmann’s usual tricks are present here: the sweeping pans in and out, the anachronistic soundtrack, sets that look straight out of a green screen, gorgeously filmed actors, music cues that repeat, etc. etc. And as if that’s not enough, he ups the ante by doing it all in 3D (a redundant, unnecessary decision, if you ask me).

Some of it works, and works well, but the cost of focusing so much on the aesthetics is that the characters get short-shrift. Gatsby, especially, comes off as little more than an icon. He carries mystique not because he’s mysterious, but because he’s supposed to. It’s not Leo’s fault, but he’s certainly not the best thing about the movie. Likewise, it’s to be expected that a man would be drawn to the adorable Mulligan, but Daisy doesn’t seem to be more than a pretty face.

Capturing the spirit

And yet, despite all this, or perhaps in spite of it, I found Gatsby to be a more than tolerable experience, and certainly not the train wreck it could have been. It’s almost as if Nick was writing my review when he says, “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

And yet, despite all this, or perhaps in spite of it, I found Gatsby to be a more than tolerable experience, and certainly not the train wreck it could have been. It’s almost as if Nick was writing my review when he says, “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

Indeed, with its impressive visuals and a soundtrack that includes such out-of-time songs as Jay-Z’s “Izzo (H.O.V.A.),” this is a film that’s fizzy fun, one that captures the spirit of its setting and the anything-goes culture of the Hamptons party scene of the Roaring ’20s.

More importantly, the film works because the source material holds up well; all of Luhrmann’s stylistic touches and tweaks (Nick is telling the whole story from a sanitarium, for example) can’t erase the compelling narrative at the center of the movie. Thank God.

I’d never go so far to call this a classic or a great adaptation (it’s neither of those things), but for what it is, with expectations lowered a little bit, the film holds its own.

This review originally appeared on Martin’s Musings.

2 comments

Dan O. says:

May 11, 2013

Good review Martin. Not amazing, but okay watch if you’ve never read the book. But for people that have read it; it will be a bit of a bummer.

Martin Lieberman says:

May 11, 2013

Thanks, Dan! I wanted to reread the book before seeing the movie, but never got around to it. I’m glad I didn’t. But now I’m definitely going to make an effort to reread the book.