The top ten is so close we can almost taste it! We hope you have been having as much fun reading this as we did compiling it. We also hope that this list has been a trigger in your going back to give a listen to some fantastic music. What a decade, huh?

Now, this is the real money. The top twenty starts now. Here are some of the most iconic albums from the decade.

Think you can guess the top three? Leave a comment here with your guesses and be entered to win a copy of any one album from this list (digital or physical CD-provided that the album is presently in print. U.S. residents only.)

If you need to backtrack, you can check out Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, and Part 8.

Okay, let’s boogie.

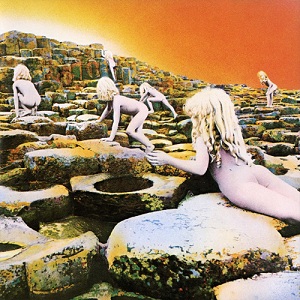

20) Houses of the Holy (Led Zeppelin, 1973)

20) Houses of the Holy (Led Zeppelin, 1973)

There’s nothing wrong with Led Zeppelin as a blues-influenced rock band. They were the best at what they did. The ultimate band of the Seventies.

Houses of the Holy represented a turning point. Not to say that the quartet was stylistically limited before, but the album has a sense of confidence and artistic daring that none of Zep’s four previous albums contained, and maybe that’s why I like it so much. As opposed to the “kick in the door” approach of Zeppelin’s first few albums, this one slides into the room coolly, for the most part. It helps that all of their left turns work so well, of course.

“Dancing Days” and “Over the Hills and Far Away” turn the volume down a little bit, but are just as masterful as songs like “Rock & Roll” and “Whole Lotta Love.” “D’yer Mak’er” is one of the first excursions (if not the first) a rock band ever took into the land of reggae, and “The Crunge” is a funk jam worthy of James Brown. You wouldn’t think of Led Zeppelin in the same league as an Ohio Players or Parliament/Funkadelic, but “Crunge” fucking grooves man. I don’t play an instrument, but I would have to imagine that Bonham and Jones were on their “A” game as the rhythm section on this track.

I’m by no means a Led Zeppelin historian. After all, I didn’t discover the band until I was in my late teens. However, Houses of the Holy ranks as one of the most important albums in my classic rock-ucation. By embracing a little bit of musical diversity, the greatest hard rock band of all time gained a forever fan in this kid from Brooklyn. (Big Money)

19) This Year’s Model (Elvis Costello, 1978)

Elvis Costello made his debut with My Aim Is True, but he arrived with This Year’s Model. Where the former album sounds like a batch of murkily recorded demos, Model all but explodes in your face from the very first moment, when Costello, sounding too keyed up to contain himself, blurts out a couple of lines before his new backing band comes crashing in; it’s almost the last relatively subdued moment on the record. A lot went into bringing about this transformation: a new studio, more time and money to spend getting the sound and performances right. But it’s the Attractions that give This Year’s Model its air of being perpetually wound up and ready to boil over. Pete Thomas’ drums clatter freely through the arrangements; future Costello nemesis Bruce Thomas plays cutting, fluid bass; and Steve Nieve’s keyboards alternately shriek and seduce. The songs Costello brought to the record gave the new players plenty to sink their teeth into. You have the hits everybody knows: “Pump It Up,” a kind of New Wave riposte to “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” and “(I Don’t Want to Go to) Chelsea,” all jerky nerves and sublimated menace. Then you have all the rest, one great song after another: “No Action,” “Hand in Hand,” “This Year’s Girl,” “Lip Service” … oh hell, just read the track listing. (Dan W.)

18. Sticky Fingers (The Rolling Stones, 1971)

In the late ‘60s or thereabouts, those upstart Rolling Stones started calling themselves the Greatest Rock n’ Roll Band in the World — and damned if they didn’t go on to prove it with one of the most astonishing creative runs in rock history. Their first release of the 1970s, Sticky Fingers is the most perfect of the Four Perfect Albums. Having shaken off psychedelia with the help of producer Jimmy Miller, and freed from the tragic millstone of Brian Jones, the Stones were suddenly a band with nothing holding them back. “Brown Sugar,” Mick Jagger’s snarling paean to miscegenation, racial abuse and other things no decent person is supposed to sing about, kicks the album off while setting a new benchmark for the band as surely as “Satisfaction” did five years before. New guitarist Mick Taylor, now firmly out from under Jones’ shadow, makes his first mark with the outro solo on “Sway,” and then adds some melancholy country licks to “Wild Horses,” a Keith Richards composition so pretty and delicate that the guitarist doubted Jagger could write suitable words for it. The two guitarists are at their best on “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” with Keith’s grinding riffs in the beginning giving way to an exceptionally sharp, Carlos Santana-worthy solo from Taylor in the middle. The second side kicks off with “Bitch,” whose bursting horn charts illustrate how the Stones could lay on the production without ever dulling their ragged essence. “I Got the Blues,” a particular favorite of Keith Richards, again shows him and Taylor in perfect complementary form, while Jagger comes to the fore for the final three numbers: the harrowing “Sister Morphine,” “Dead Flowers” and “Moonlight Mile.” From start to finish, there isn’t an ounce of fat on this album — note for note, the most satisfying the Stones ever made. (Dan W.)

17. Bridge Over Troubled Water (Simon & Garfunkel, 1970)

Not with a whimper, but with a bang. So ended the recording partnership between Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel in 1970. Like former lovers forever attracted to each other, both lived separate lives and came together for quickie reunions every so often.

Their most significant shared moment together was the masterful album Bridge Over Troubled Water. Already enjoying success as American folk-rock heroes, Simon & Garfunkel had street cred from playing the Monterey Pop Festival, recording a top-selling soundtrack and Art’s burgeoning, but never fully realized, acting career.

Garfunkel’s tenor, Simon’s deeper, harmonizing tones and moments of pop music bliss continue defining the entire genre decades later. Paul Simon’s songwriting chops allowed their last studio album together to flow from ballads to pop to their nostalgic folk roots. They even included a live cover of The Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love”, which became a fan favorite.

At odds in the past, the duo’s animosity bubbled over during the recording of Bridge. They turned in an incomplete album, never agreeing on a final track, and debating the arrangement of the famous title track. The world’s best studio musicians created a huge sonic canvas that allowed the talented singers flexibility. Drummer Hal Blaine and keyboardist extraordinaire Larry Knechtel were joined by Fred Carter buttressing Simon’s guitar. All were top musical talents. Carter had already played with Dylan, Baez and Waylon while Hal Blaine’s beats had been an integral part of The Beach Boys, Elvis Presley’s and The Mamas and the Papas records for a decade.

This supergroup and Simon’s unique take on American life created an album that won six Grammys, often while competing against The Beatles’ Let It Be. They also enjoyed huge singles success, such as the title track, “The Boxer” and “Cecilia”. But it was Bridge Over Troubled Water’s title track that made this album so special. The song became an immediate classic, winning Record and Song of the Year Grammys in 1971 and netting Aretha Franklin a Grammy for her cover version just 12 months later.

Simon and Garfunkel once sang of old friends, and the years since their breakup have shown that they are willing to be friendly when the timing and dollars are right. But pop music with no Brian Wilson, no Beatles, and no Simon and Garfunkel sure seemed pretty bleak as 1971 dawned.

Paul and Art left behind a heck of a going away present. (George B.)

16. Some Girls (The Rolling Stones, 1978)

Some Girls got the Stones in a world of trouble. From the actresses (like Lucille Ball) who objected to their visages being used on the album cover, to the infamous “black girls just like to fuck all night” line in the title track, Some Girls courted controversy that no Stones album generated before or since. From a less legally or racially incendiary standpoint, the opening track/first single “Miss You” was largely derided for capitulating to the then-dominant disco style permeating radio airwaves.

Regardless of all that, Some Girls is the last truly great original Stones album (Tattoo You was more of an odds and sods thing)-their response to feeling like the old guard for the first time in their careers. New wave, punk and disco were capturing the imagination of the youth, and Mick, Keef and co. needed to prove that they could still hang. Prove, they did. The line of classics on Some Girls is as long as my arm-“Before They Make Me Run,” “Shattered,” “Beast of Burden,” and yes, “Miss You.” That last song is as good as rock/disco ever got. Two more solid if not great albums followed, and then…tour after tour after tour, with Stones albums only appearing to sop up a little extra cash before the fellas hit the road. (Big Money)

15. Dark Side of the Moon (Pink Floyd, 1973)

800 weeks on the charts. Tens of millions sold. A permanent spot on the radio. A place in the home of just about every classic rock fan in existence. More joints smoked to it than any other album released in the ’70s. OK-we can’t confirm that last one, but Dark Side of the Moon is truly iconic.

It’s at turns wacky (the album at least partially inspired by the mental illness of founding member Syd Barrett) and extremely commercial. “Money” (the album’s best known song and one of only two Floyd tracks to reach the Top 40) brought the word “bullshit” into the Top 40 for the first time and introduced the ring of a cash register to the library of percussion sounds. “Time.” “The Great Gig in the Sky,” “Us & Them.” All classic songs that form a cohesive suite the way albums used to…remember those days?

Plus, it syncs up to “The Wizard of Oz.” Dude, I totally tried that one day! No, I didn’t. But I bet you have. (Big Money)

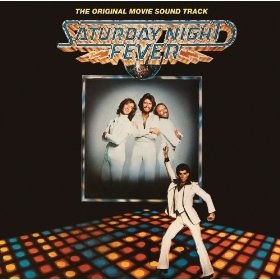

14. Saturday Night Fever (Original Soundtrack) (The Bee Gees & Various Artists, 1977)

14. Saturday Night Fever (Original Soundtrack) (The Bee Gees & Various Artists, 1977)

There are two striking things about the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack when you listen to it now: first, how it perfectly fits a vision of the late 70s, no matter how into disco you were; and second, just how many hits SNF spawned or represented on the pop charts. With ten songs that charted either prior to or in the wake of this soundtrack’s release, SNF was not only the score to a popular movie, but it became a musical time capsule of where disco came from and where it was going. From pop powerhouse the Bee Gees, side one of the vinyl release became a mini greatest hits compilation, with “Stayin’ Alive,” “How Deep Is Your Love,” “Night Fever,” and “More Than a Woman” all forever linking the movie and the group together.

Hits aside, SNF is also a testament to how disco united people through music, with components of pop, R&B, salsa, calypso and even classical (“Night on Disco Mountain”) all meeting on the dance floor. Even the themes of the songs were universal, kicking off with track one “Staying Alive”: “Whether you’re a brother or whether you’re a mother/You’re stayin’ alive, stayin’ alive.” If America was a melting pot, then the dance floor was the place where the flavors mixed and mingled. In fact, if there is one piece of diversity missing, it would be the lack of female voices on most of the album, although Yvonne Elliman’s “If I Can’t Have You” stands strong amidst all the men. While most of the individual tracks do stand well on their own, it is the combination of multiple genres of music, instrumental tracks that told their own stories, and the undeniable magic of a group at their prime (the Bee Gees) that make this a must-own album of the 70s. (John H.)

13. Innervisions (Stevie Wonder, 1973)

13. Innervisions (Stevie Wonder, 1973)

Welcome to story time with Uncle Big Money. In the summer of 1982, I was a 6 year old who’d discovered the work of Stevie Wonder for the first time. “That Girl” and “Do I Do” were riding high on the charts, and I was entranced. Being a kid with no sense of financial restrictions, I asked Valerie, my uncle’s girlfriend, to buy me a Stevie Wonder album so I could play it on my new Fisher-Price record player. A few days later, she brought me a copy of Innervisions. Even though I was initially chagrined that I didn’t receive a copy of the then-new Original Musicquarium album, I quickly fell in love with Innervisions, and thirty years later, it’s arguably my favorite album ever released. Thanks, Valerie. I’d thank you in person, but I don’t know where the hell you are.

There are at least five Stevie albums that could be any other artist’s magnum opus, but Innervisions is Stevie’s magnum opus. Perfect from beginning to end-it contains some of the best singing, musicianship and songwriting in existence. What’s incredible to believe is that Stevie was barely 23 when Innervisions was released. While most 23 year olds are still trying to figure themselves out, Stevie was writing songs like “Golden Lady” and “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing.” There’s a song on Innervisions that covers just about every mood or feeling there is. Want to know what it feels like to be in the throes of drug addiction? Check out the woozy “Too High.” Mellow and meditative? “Visions” will take care of you. Heartbroken? “All in Love is Fair” is a master class on how to write and sing a love song (or an un-love song, as it were.)

The sense of spirituality Innervisions carries on songs like “Higher Ground” and “Jesus Children of America” would serve Stevie well when he was involved in a near-fatal car accident shortly after the album’s release. Very literally. Stevie had been in a coma, and didn’t come out of it until a friend sang “Higher Ground” directly in his ear. Now, that’s the power of music.

Innervisions won Stevie the first of three Grammy Awards for Album of the Year, and stands as the crowning achievement in the career of one of the best to ever do it. (Big Money)

12. Born to Run (Bruce Springsteen, 1975)

According to legend, the title track of Born to Run was nearly declared the official song of the State of New Jersey. The irony of this legend (which seems to at least have some basis in fact) is of course that the song is about getting the hell out of New Jersey—“it’s a death trap, it’s a suicide rap, we gotta get out while we’re young.” The title track is an absolute masterpiece, and there may well be three songs on the album that I like better. Diehard Springsteen fans tend to like his three subsequent albums better—Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978), The River (1980) , Nebraska (1982)— but I always preferred Born to Run because of its sonic scope. Before he adopted his “stripped down” sound, he had to have something to strip down in the form of enormous soundscapes and theatrical melodrama that rival anything that Queen or Meatloaf offered. (It is no coincidence that two E Street Band members are musicians on Bat out of Hell (Epic, 1977)). This melodrama reaches its apex during the closing track, “Jungleland,” but the grandiose piano arpeggios of “The Professor” and the soaring sax playing of the “Big Man” in that song would not have their power without the album’s humble beginnings. “Thunder Road” starts with a harmonica and a simple piano melody. The lyrics are picturesque Americana: “The screen door slams, Mary’s dress waves. Like a vision she dances across the porch as the radio plays.” The movement of the album, both lyrically and sonically, from that porch to the urban chaos of “Jungleland” is enormous, but the question of whether crossing the river to the Jersey side was worth it remains unanswered. (Michael Mario)

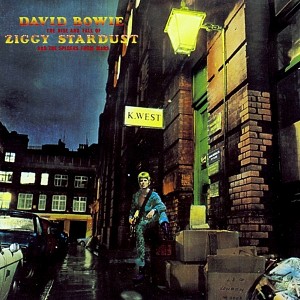

11. The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust & the Spiders from Mars (David Bowie, 1972)

11. The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust & the Spiders from Mars (David Bowie, 1972)

David Bowie’s songwriting got consistently more interesting from the time of his overly poppy psychedelic debut through 1971’s acclaimed Hunky Dory. With that growth in innovation came greater acclaim, but it wasn’t until his fifth studio album that Bowie launched into the stratosphere (or did it launch him from the stratosphere?). Ziggy materialized in an era when concept albums were the norm. Tommy was only three years old; Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick was released three months prior; The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway would be released two years later; The Kinks were plopping out concept albums for years; and things got uncomfortably grandiose when proggers like Yes, Styx, and The Alan Parsons Project had their way with the form. What’s unique about Ziggy Stardust is that it manages to construct a narrative concept (albeit a loose one) and avoid the bloat that goes along with so many concept albums.

The album opens with vivid imagery of a dystopic Earth whose existence is waning, presumably due to our own ignorance. Then, a sexy androgynous rock star beams down to comfort us and give us hope. Yet all the soul love, glitter, and pressing of space faces provides only momentary reprieve: by album’s end, the impulse is still to off yourself. “Rock n’ Roll Suicide” could be a shallow collection of cliches regarding the excesses of stardom. But instead, Bowie paints a stark picture of the subject’s inner psyche (there’s something incredibly sorrowful about the line “You walk past a cafe, but you don’t eat when you’ve lived too long”). But here comes Ziggy with the real redemption, spewing messages of affirmation and resilience: “YOU’RE NOT ALONE!” / “I’ve had my share, so I’ll help you with the pain.” / “GIMME YOUR HANDS! ‘Cause YOU’RE WONDERFUL!” As told by Bowie, the story is far more complex and perhaps not as happy of an ending as I’ve laid it out here. But that’s how I read it at age 15, and I’m sticking to it.

Ziggy Stardust is one of those albums – like Sgt. Pepper before it and Thriller after – that became much more than the music contained on its two sides. The Ziggy character became larger than life – certainly larger than David Bowie. Watching Bowie’s audience in concert footage from this era finds teenagers seemingly worshiping a rock star that at least looks like an alien, taking his lyrics as gospel, and finding solace in songs that seem tailor-made for addressing the sense of social isolation intrinsic to being a teenager. That kind of hero worship likely didn’t sit well with Bowie, much less the tedium of very literally playing the same “character” each night. It’s inevitable that someone as image- and career-conscious as Bowie would have to kill off Ziggy rather quickly (“Not only is this the last show of the tour, but it’s the last show that we’ll ever do”). As is now common knowledge, Bowie went on to metamorphose many times throughout his career, and frankly, he also went on to produce far more interesting music. Yet Ziggy Stardust never lost its lustre. And over thirty years later, it’s the album that continues to define David Bowie more than any other. (Dr. Gonzo)

5 comments

John says:

Mar 22, 2013

I think someone could be forgiven for not knowing some of the albums further down the list, but if you don’t know these ten albums, then gets to listenin’! Great job all around, y’all!

Gonzo says:

Mar 23, 2013

The 12″ version of “Miss You” is incredible. I actually also dig Dre’s remix from ten or so years ago. And I totally agree that Some Girls is their last great album. Actually, I’d argue that it was also their first great album since Exile. Goat’s Head Soup, It’s Only Rock and Roll, and Black & Blue are so spotty – there’s probably one album’s worth of great material between them.

Gonzo says:

Mar 23, 2013

And yes…yes I have synched up Dark Side to the Wizard of Oz.

Big Money says:

Mar 24, 2013

I dig all three of those albums, but agree that they’re somewhat spotty.

I thought about mentioning that Dre remix, then I was like…eh…I thought it was OK, though.

Big Money says:

Mar 24, 2013

I am not surprised!