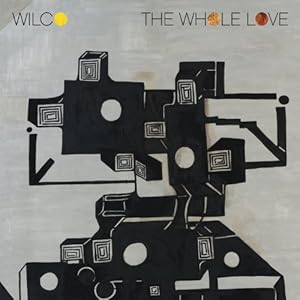

It’s interesting, really, that Wilco’s latest album begins with the dissonant, twitchy, seven-and-a-half minute “The Art of Almost”. Not that it’s weird for Wilco to record long, strange songs that culminate in discordant, cacophonous jam sessions – “‘Spiders (Kidsmoke)’!,” everyone who’s ever heard the alt-country pioneers’ A Ghost Is Born record just yelped in unison – but because, once you get past the opening track’s mind-melting uniqueness, The Whole Love is really quite accessible.

It’s interesting, really, that Wilco’s latest album begins with the dissonant, twitchy, seven-and-a-half minute “The Art of Almost”. Not that it’s weird for Wilco to record long, strange songs that culminate in discordant, cacophonous jam sessions – “‘Spiders (Kidsmoke)’!,” everyone who’s ever heard the alt-country pioneers’ A Ghost Is Born record just yelped in unison – but because, once you get past the opening track’s mind-melting uniqueness, The Whole Love is really quite accessible.

Lots of people have followed Wilco’s career trajectory, after all; their 2001 record Yankee Hotel Foxtrot may very well be the most acclaimed album of its decade. And with good reason: a decade later, it holds up as a pretty perfect record, with the richest set of melodies this side of Abbey Road. But it also marked a turning point for Wilco – they followed up Foxtrot with A Ghost Is Born, which took Foxtrot‘s method of being slightly more off-kilter (at least compared to the crackerjack traditionalism of their first three records) and ran with it all the way into Crazyville, and followed up that record with Sky Blue Sky and Wilco (The Album), both of which read as self-aware stabs at normalcy, and both of which succeeded a little too well. For a spell, Wilco were conjuring up the dreaded “dad-rock” adjective; that is to say, there was nothing inherently wrong with what they were doing, it was just a little safe, a bit on the pedestrian side.

Enter The Whole Love. Wilco’s constantly in flux lineup seems to have settled into something workable for the time being, which is nice, and as a result, Wilco sounds like a real collective here, and not like Jeff Tweedy and His Wil-Tones. But more important are the songs; The Whole Love sounds a lot more like an album that one could title Wilco (The Album) than, well, Wilco (The Album), because it’s an album that hits upon all of Wilco’s considerable strengths, and even, charmingly enough, a few of their weaknesses. Which makes it perhaps the most essentially “Wilco” album of Wilco’s career, even if it can’t in good conscience be called their best.

The Whole Love is bookended by the two most experimental tracks here – the aforementioned “The Art of Almost” is skittish and almost-funky; closing track “One Sunday Morning (Song For Jane Smiley’s Boyfriend)” is miles removed from “Almost” with its folksy acoustics and evocative piano figures, and would be absolutely par for the Wilco course if it weren’t a constantly-morphing, twelve-minute behemoth, a soothing early-morn opus that breaks like dawn over the horizon. It’s the sound of sunlight filtering in through the blinds, and changes gears almost imperceptibly, settling into a low-key country shuffle by song’s end; it goes down so easy that “The Art of Almost” actually feels significantly longer, despite being five minutes (or half a Dream Theater song, or eight Minutemen songs) shorter. In between, Tweedy’s songwriting revisits several key exhibits in the Wilco Museum of Modern Pop Art: the addictive country-rock four-on-the-floor stomp of “Dawned On Me”, for example, feels like Being There‘s best moments, like hearing “Outtasight (Outta Mind)” for the first time, except it’s got a bizarre buzzsaw guitar floating in and out of the mix like it’s on loan from A Ghost Is Born. (There’s also a too-brief whistling solo straight out of divine early track “Red-Eyed and Blue”.) And, of course, 1998’s impeccable punch-drunk 60’s-pop pastiche Summerteeth isn’t forgotten: “Capitol City” is some of the most mellifluous, ambling mid-period Beatles-pop this band has ever laid to wax, and about halfway through, features some of the most crackerjack gangland harmonies of Wilco’s career to boot. Wilco crank out a classic-rock barnburner with an earworm chorus in “Standing O”; bittersweet Iron & Wine-y dusk-folk suits them nicely on “Black Moon”; “I Might” is insistent and repetitive, but gains points for intermittently borrowing the keys from “96 Tears” and employing them to delightful effect.

All this to say: The Whole Love is easily the liveliest, wiliest, and most energetic Wilco have sounded in these ten post-YHF years. And now that Wilco sounds like they’re back into making excellent music instead of merely very-good music – and now that they sound like they’ve curbed, for the most part, some of their more peculiar musical flights of fancy – we should all be back in the business of taking note. After all, R.E.M. have called it quits; we’re gonna need elder southern statesmen with a knack for maddeningly addictive (if lyrically nonsensical) alt-rock gems, and as if they dislodged the sword from the stone, this version of Wilco seems more than game for taking up the mantle.

Grade: A-

1 comment

Dennis says:

Sep 28, 2011

Totally agree – I’m really enjoying this record. Easily my favorite release of theirs since YHF. The new stuff sounded great in concert and blended right in with older material.